This may seem like a strange title for an article in a world where gold is over $1000 an ounce and oil is at $110 a barrel, causing people like my buddy bonddad to write articles entltled, "What Inflation?", and this is somewhat a response to his latest post,

Why Isn't the Bond Market Selling Off From Inflation Fears?.

The very best analysis of the issues in our new economic world was recently set forth, imho, by Prof. Bred DeLong, who described 3 types of crises:

The first -- and "easiest" -- mode is when investors refuse to buy at normal prices not because they know that economic fundamentals are suspect, but because they fear that others will panic, forcing everybody to sell at fire-sale prices.

The cure for this mode -- a liquidity crisis caused by declining confidence in the financial system -- is to ensure that banks and other financial institutions with cash liabilities can raise what they need by borrowing from others or from central banks.

....

In the second mode, asset prices fall because investors recognize that they should never have been as high as they were, or that future productivity growth is likely to be lower and interest rates higher. Either way, current asset prices are no longer warranted.The problem is not illiquidity but insolvency at prevailing interest rates. But if the central bank reduces interest rates and credibly commits to keeping them low in the future, asset prices will rise. Thus, low interest rates make the problem go away....

But as long as the degree of insolvency is small enough that a relatively minor degree of monetary easing can prevent a major depression and mass unemployment, this is a good option in an imperfect world.The third mode is like the second: A bursting bubble or bad news about future productivity or interest rates drives the fall in asset prices. But the fall is larger. Easing monetary policy won't solve this kind of crisis, because even moderately lower interest rates cannot boost asset prices enough to restore the financial system to solvency.

DeLong concluded by noting that the Fed initially believed last August that it was confronted with a liquidity crisis only, but very quickly determined that it was actually facing the second type of crisis. Nobody was seriously considering the third type of crisis.

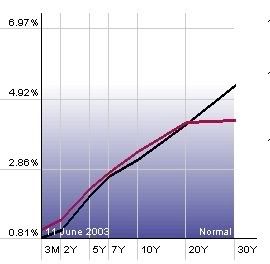

There is some reason to believe that the Federal Reserve is actually pursuing the "least worst" alternative (since there are no good ones), and to that point I give you the following graph of the US treasury yield curve:

This yield curve graph brings us good news and bad news: the good news is that the red line, showing the yield curve as of yesterday, is strongly positive. A positively shaped yield curve normally means good things for the economy about 12 months out. In order to achieve that, though, note that the bond market now expects the Fed to cut all the way to 1%, and pretty quickly too. If we turn out to be in a type two crisis, that's good news.

The bad news? That would be the black line. That represents the yield curve from June 11, 2003, which is the lowest the yield curve has been in about half a century. And what does that yield curve mean? Here's a link to an article from Business Week magazine on May 21, 2003, entitled Deflation: Avoiding That Sinking Feeling, Are we entering a period of declining prices? Smart business owners should hope for the best and prepare for the worst .

In other words, the bond market is beginning to worry that we may be approaching Prof. DeLong's third type of crisis. The bond market is worried about deflation.

Comments

more background on Deflation

Wikipedia on deflation, going to the Liquidity trap article:

IMF forum on deflation, bond yield curves and the liquidity trap.

I still don't understand all of this except the word bubble economy and the word pop

Hope the links help others but I think we're in crisis 3 although I don't get how this causes deflation when foreigners own US debt and assets and the tanking dollar in a global economy.

I thought muni bonds were a good hedge against deflation.

I'm an amateur who manages his own IRA. When I saw the coming crisis, my strategy was kind of like a bracket. I bought gold, silver and Euros as a hedge against a hyperinflationary collapse of the greenback and I bought muni-bonds as a hedge against a depression style deflationary collapse in asset value.

My understanding was that in a time of extremely low interest rates and non-existent yields from stocks, the demand for munis would sky-rocket. All other things being equal, a muni that currently pays a 4% yield would appreciate in value if interest rates were around 1%; this is because there would be increased demand for the higher yield of the munis. So, the price of munis would have to rise, until their effective yield had dropped to the point that demand for them had equilized.

So, why does the Bond Market fear deflation (besides the collateral damage it will do to the economy)?

hello

very nice article thank you very much.... evden eve