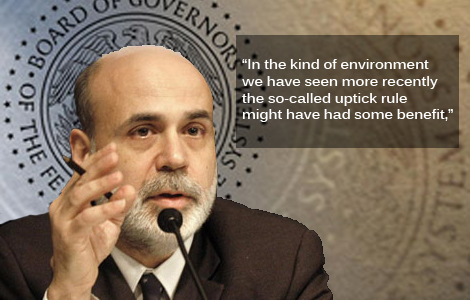

Today I was watching Federal Reserve Chairman, Ben Bernanke testify before Congress. One of the committeemen brought up the uptick rule to him, and whether we should bring it back. He gave one of those cryptic answers where one wondered whether we should or shouldn't have it.

(As reported from Bloomberg, on the 25th of February, 2009.)

A primer on the uptick rule

So what exactly is the uptick rule? Why is it so significant and why did they eventually get rid of it? To understand that you have to go back to prior Franklin Delano Roosevelt became President and the establishment of the New Deal and the Securities & Exchange Commission. Back then the stock market was much more wild and prone to manipulation than it is today.

Keep this in mind, prior to the SEC and it's regulations, one could purchase a stock with 90% margin, that is you only had to put down say $10 to control $100 worth of stock. This gave individuals and groups massive leverage to push prices where they wanted. It also was much easier to get wiped out. You had individuals like Jessie Livermore and other "stock operators" coming in with massive orders to bring down a stock's prices. Besides individual "plungers" you also had organized stock pools, were a group of individuals would try and corner the market on a stock to manipulate. Often these manipulations were of a fraudulent manner, like insider trading.

When you had these bear raids, that is efforts to cause a collapse in the price of a stock, it would often be swift. But before I continue, I almost forgot one other piece of fundamental trader lingo, that is going "short" and going "long." For the uninitiated, going "long" a stock is simply the classic buy at what you think is a low price and sell at a higher price. Shorting a stock is the opposite, sell high buy low. Yes, you can sell something you don't own, but only in the stock markets (actually there are situations where this isn't possible, but that's for a different day). Bear raids were these shorting episodes. Back then you could short a stock, say at $50, and then as it dropped to $49, you would short some more. Rinse...and repeat...rinse and repeat. Pressure would build and build until suddenly, you had your big drop. These plungers were so ferocious, that back then, it was not uncommon to see a stock lose half it's value.

It was this type of activity that aggrivated the situation during the Crash of 1929. Every time the market tried to recover, that only made the operators short even more stock (remember, leverage was 10-1 back then). In the aftermath of the fateful October week, one of the first things the SEC did was inact the Uptick rule. The Uptick rule stipulates that no shorting can be done on a stock until the price has moved one tick in a positive direction. Remember, prior to a few years ago, stock prices didn't move in penny incriments, they moved in fractions and often the average "tick" was 1/8th (or $.12). If one wanted to short IBM, and it was trading at $100, you had to wait until it traded at $100 1/8th. The Nasdaq opted for a slightly altered version, that is instead of the last traded price, it had to be the last bid (price one wished to buy at) price.

It was felt that this would serve as a delaying action against the bears. If one had to wait for the price to go up, it was thought, that would possibly discourage shorting. Indeed, a series of price increases may make a trader think otherwise, why go short if this is the beginning of a bull run to a new high? But also, in situations where you had massive drops in price, say one price traded for XYZ was $50, and then the next one was $40, the uptick rule served as sort of a circuit breaker. If the market was heading southward, any increase of pressure from short sellers would be put at bay until they could get, say for example, a $40.01 price before they could do anything.

The Uptick Rule in Today's Era of Decimalization

Back in the year 2000, the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) began a move towards quoting stock price changes in pennies versus fractions. The SEC had demanded that by April of '01, all exchanges trading equities must move towards decimalization. The reasoning behind this was so that the average investor could get a better price. Prior to this, as was mentioned above, the average Bid/Ask spread was essentially $.12. If you purchased 100 shares of stock, one was essentially starting off with a loss of $12. Today, the average Bid/Ask spread is between $.01 to $.03 in your most liquid stocks during the normal trading hours.

But because of this, we've essentially cut down the waiting period for the bears to short a stock. Instead of waiting for that 1/8th move, for example, all they have to do is wait for a penny...a single penny. Anyone can "bid up" a stock to meet that penny demand. In this market, the Uptick rule, as it stands, is useles. But should we even have an Uptick rule? The SEC wanted to know if the thing was useful anymore and did a pilot program removing it from certain stocks. What it found was that in it's present form, it was indeed useless. On July 6th, 2007, the Securities & Exchange Commission eliminated the 70-year old regulation.

The Argument For the Uptick Rule

Almost immediately, there was an outcry, largely from market veterans, to reinstate the old rule. One of the first was Muriel Siebert, the first woman to own a seat on the NYSE, questioned the decision following the recent market turmoil.

(As reported in the New York Times on the 26th of August, 2007)

Speaking of market turmoil, please take a look at the chart above. The data, courtesy of Barchart.com, is a graph of monthly prices of the S&P 500. Please note in the middle of '07, that is when the Uptick Rule was effectively gone.

One can immediately tell what began to transpire. July 2007 just about marked the "top" of the post 9/11 bull run. The first to go was the financial sector. Oddly enough, the end of the Uptick rule coincided with the beginning of the mortgage meltdown. Below is a chart of the Financial SPDR (An exchange traded fund that is made up of financial stocks, a good proxy for the sector).

Crazy, how from July or so, the financial sector hasn't really recovered. For a small while, one of the rumors or gossip amongst traders was that Bush had friends who knew the you-know-what was going to hit the fan. That Christopher Cox was made to open up the flood gates to allow the Administration's friends to profit from the incoming doom. Of course, this is all speculation. Still, removing the Uptick rule couldn't have come at a better time for someone wanting to take advantage of the financial sector's implosion.

As you probably have guessed, I'm in favor of the Uptick rule. Don't get me wrong, I'm all for shorting stocks, I do it, everyone does it. Shorting a stock is natural, if a company is bad or near death, an investor or trader almost has an obligation to take advantage of the situation. The argument for removing it, was that it was useless (penny move..oooh), and that one must let markets operate naturally.

But I think it's also important to not let volitility to get out of control. Volitility in itself isn't bad, without it, even the buy-and-hold crowd wouldn't make money. But the big 'V' is also a double-edge sword. If something must fall, it will fall, but forcing a fall beyond what it would have normally fell is almost reckless. Of course the argument then becomes how does one know what the normal rate of a decending stock price?

At the end of the day, markets are irrational, I don't give a damn what the Ayn Rand crowd things. Economics, to me at least, has always been psychology with a lot of stats and math thrown in. Human behavior is one of the largest components in equity and commodities markets. Fear, be it for something reasonable or irrational, takes hold almost on a daily basis. People act strange when they see their position suddenly lose X amount. The Uptick rule allows folks to cool off for a bit, and assess the situation.

I know what you're going to ask. What about that decimal ruining the effectiveness of the regulation? Well we can take this one of several ways. First, we could impose a large Bid/Ask spread, that is instead of a penny difference, we make it something else like say a nickel or even a dime's worth. Yes, we would be approaching the old 1/8th spread, I understand. A second thing we could do is impose an artificial advance rate, say no shorting can take place until the stock moves $.05. You wouldn't have that large spread, but the problem here is that some stocks are more volitile and others just flat. A third option would be to guage the Uptick threashold to the implied volitlity of the individual stock.

Whichever way we go, we should, as Ms. Siebert and others have noted, bring back the Uptick rule. Markets are volitile enough as it is. Why make the situation worse for the average investor?

Comments

I guess I'm still amazed

That short sells are legal at all. I'm for something bigger than the uptick rule. NO SALES ALLOWED WITHIN 5 YEARS OF ORIGINAL PURCHASE OF STOCK.

In other words, keep the good point of the stock market (a way for companies to get money out of investors) and eliminate the bad point (gambling on price speculation). End volatility at all by reducing trade volume.

-------------------------------------

Moral hazards would not exist in a system designed to eliminate fraud.

-------------------------------------

Maximum jobs, not maximum profits.

That's impossible

You cannot forbid a sale of a stock. What if someone needs to sell their stock to raise money? Say someone who is retiring soon or someone who needs to use that money to pay for college? Also, in order to buy stock, someone needs to sell you that stock.

Rational decision making

Then they shouldn't have purchased stock to begin with, they should have kept it in a more liquid form.

These are things people plan a half decade in advance- they're forseen expenditures.

That's what Initial Public Offerings are for. What this means is you plan long term instead of short term, that's all. It isn't a total "forbid people to sell", it's "you can't sell until you've held the stock for five years or more".

-------------------------------------

Moral hazards would not exist in a system designed to eliminate fraud.

-------------------------------------

Maximum jobs, not maximum profits.

That even makes less sense!

Wait, why when the stock would represent a good investment opportunity? Also, why punish someone who wants to make a profit, that seems rediculous. You're eliminating the whole reasoning to buy the stock to begin with! Seebert, you also contradicted yourself with that. You claim to that it should be manded essentially, to have it long-term in focus, for the investment. Ok, so assuming they keep it "long-term", they eventually have to unload the stock to someone else. Guess what, seebert, that's called selling a stock!

In regards to liquidity, stocks are VERY liquid compared to many assets. One can get out of a bad position in an equity faster than say one can sell a piece of real estate. Who, I would like to know, should ban people from their investment decisions? Frankly, what is needed is proper financial education, be it in our schools or what have you. If the investment product seems dodgy, then don't invest in it. If you do, and lose money, well it's your own damn fault.....unless you can sell it! But wait, they wouldn't be able to under your rules.

They can plan for what they want, but the intelligent investor also reacts to a changing enviroment. Half a decade ago that Blue Chip superstar, General Electric, was considered a great investment; the stock traded in the mid-30s through late 20s (about $28/share). Today GE trades at a fraction of that, about the equivalent to a Domino's pizza. Investors who were due dillegent started to move out of GE at a desginated stop loss price of their choosing. Many, sadly did not. Yet, under seebert's rules, well you should've planned out for that, want to sell as it starts to go down? Nyet to that, comrad!

Two things here. First, if the seebert no-can-sell rule is imposed, that IPO is going to go over like a lead balloon. What investor in their right mind is going to take a chance on a company popping their stock market cherry when they know they won't be able to sell that stock? Also, IPO sales are already regulated, those who got equity stakes prior to the date have to wait about 18 months until they can start to sell.

Secondly, what if the company doesn't want to dilute the shareholders? You know, the company may decide to go the corporate debt route instead of issuing new shares. That is why you have a secondary market like the NYSE and Nasdaq, amongst others. Markets provide an important service for those looking to invest their money. In order to facilitate what you want, you will move the action from the exchange to the investment banker. Someone like Goldman Sachs would immediatly become both the folks financing the sale and product introduction, but also the exchange, and quite possibly the broker as well. Frankly, I don't want to give them THAT much power.

With volatility

Risk based opportunities are not "good investment", they are at best speculation and gambling.

The reason to buy stock *should* be INVESTMENT. In other words, you believe in a company so much that you want to own a piece of it and get a portion of the profits. If that is your reason for buying stock, then you want to hold on to it as long as possible.

If you've got a true long term focus- then no, you don't want to "unload it on somebody else". You want the company to pay you dividends, and that's how you get a return on your investment.

Oh, sure, someday your heirs may wish to sell it, because they no longer believe in the company. But then, somebody else might believe in the company enough to buy it.

Which is against the common good of having a stock market to begin with.

All "investment products" are dodgy. All contain risk, and are not stores of value. As the old logger once told me- if you buy something from a man in a suit, you can be sure than most of your money is going to pay for the suit.

Under my rules, GE would not have gone "up" or "down" to begin with- the stock would still be trading for what it did at IPO. The money would be made off of dividends in that stock. That's REAL capitalism- puting capital where it can make money, not gambling on some made-up market price of a stock that has no reality behind it from day to day.

The type of investor that every company really wants- the type that will stick with the company through thick and thin, and will do their damndest to help that company be a success. Why would a company want an investor whose sole purpose is to sell off at the first bump in the road?

And I'm saying that should be longer- that we need to return to the real SOCIAL purpose of investing to begin with. If you don't believe in or understand *everything* about what a company is doing, you shouldn't be investing at all.

Then that is that company's decision to forgo new investment. They don't want you playing in their garden, so why do you want to force your way in?

Not neccessarily. What I want to move the action to is the company itself- who should have a say in who can invest and who can't. In fact, ideally, I'd like to see all stock sales be private, with no anonymity in the market at all.

Why would any company pay Goldman Sachs to do that, when they could do it themselves for less?

-------------------------------------

Moral hazards would not exist in a system designed to eliminate fraud.

-------------------------------------

Maximum jobs, not maximum profits.

Not a realistic take on risk, my friend.

You do realize there is no such thing as no-risk investment vehicles, right? Every investment has an element of risk to it. Even US savings bonds, despite what you've been told, has an element of risk to it. There is nothing to say that Uncle Sam won't default on it's debt.

Seebert, please pick up a copy of the Black Swan, or When Genius Failed, or Against the Gods. Trust me, my good man, there is NO such thing as NO risk. Even insurance companies establishing policies for what they deem as "safe" clients, their actuaries know there is still a chance.

As for the other things, seebert, frankly you need to take a corporate finance class. And if you have, re-take it. What you propose is simply impractable. Your dividend model would lead to diminishing returns and eventually insolvency. How? If, as you say, the company should reward shareholders through only dividends, then if a company needs more capital it will have to issue more stock.

Increasing the supply dilutes the existin shareholder base, this is also one of the fears of the banks currently under TARP. Now if you have to distribute dividends, then you are taking money away from other capital investments. Secondly, as you increase the float, the yield decreases. Do the math. If there are only one-hundred shares on a stock with a par at $10, and it pays out $1 in dividends, your yield is 10%. Now what do you think happens when they issue another 100 shares? Remember now, they set aside a certain amount for dividend payments. The new shareholders aren't going to get $1/share, and neither will the original holders of the first 100 shares. Eventually you get to a point where they will not be able to attract investors to meet the firm's capital needs.

education, classes, financial awareness

This is a very good point. For the Populace to wake up it is assumed they have the ability to self-educate, look up concepts, systems on the web, read economics texts, learn.

I'm doing that all of the time and if I say something stupid, wrong, incorrect, well, someone point it out but to not be self-educating is probably the reason pundits like Glenn Beck and many others (I'll take Olbermann on the left because he seems quite full of it also) can take one fact, or one graph and then use that fact to spin some inane policy recommendations, often crafted by some corporate lobbyist think tank or special interest group also not founded firmly in economic fact or even historical data.

REALLY the last post

You're completely right. I have no stomach for risk, and no wish to invest in a business that isn't either already profitable enough not to need my investment, or that I do not believe will be profitable enough not to need future investment.

Thank you for the recommendation of books. The rest I've answered in my own blog, which is linked to off this account. I decided you deserved more of an answer than me just dropping off the universe. I will be logging out now and not logging back in, as it is clear that what I see as populism and protectionism is completely a different set of values than is "economic reality".

-------------------------------------

Moral hazards would not exist in a system designed to eliminate fraud.

-------------------------------------

Maximum jobs, not maximum profits.

you do not have to leave Seebert

we're asking you to think things through as well as think before commenting.

Uptick rule is worthless

Much of the volatility of the stock market is driven by trading programs, not a few speculators. Automated trading programs cause huge swings by measuring the technicals of a stock or stock index and make decisions based on that.

The old idea of one person controlling a huge percentage of a large company and being able to manipulate the stock is, in most cases, obsolete.

There is very little rhyme or reason to the market any more. Informed decisions based on good fundamental data will be rendered worthless if an automated program decides that the technicals warrant a move opposite of what you have chosen. The so-called 'reasons' espoused by reporters for why a stock moved a certain way are always after-the-fact guesses with no basis in reality.

Unfortunately I can't even offer a solution to this problem. The government gives incentives to invest in the stock market (via 401(k) and similar programs), and mutual funds control too much money. The market has been grossly overvalued for a long time because funds have to have a certain amount of money invested. This is like forcing water into a balloon.

Back to the uptick rule, people gamble on many things. Buying and selling are just terms when it comes to speculators. There is very little 'ownership'. All that matters is that the amount bought and the amount sold are equal in the end. Why not let the speculators do their thing? I know far more people who have lost money by trying to 'beat the market' than I do who have gotten rich off of it.

Losing money & getting rich without production or R&D

The problem isn't whether the speculators win or lose. It's that as a society, we've lost the effort that the speculators put into the stock market that could be better used on other things. Take David Li, the quant who gave us this horrid piece of fraud to begin with. What if his genius had been used in bioscience instead of the relatively useless financial market?

Even worse than that- while the stock market *does* have a single useful function in our system of matching investors to companies that need capital, the volatility of speculative trading is highly inefficient and drains capital that could be better used on R&D out of the balance sheets of companies on the market. I've personally had 12 very useful projects killed by IPO, because once on the market, R&D is viewed by investors who KNOW NOTHING about the industry as just a cost, not as an investment in future production.

So while I agree with you that the uptick rule isn't necessarily a solution to volatility, buying and selling without ownership (short selling) and other forms of speculation are wasted human effort and capital that could be put to MUCH better uses.

-------------------------------------

Moral hazards would not exist in a system designed to eliminate fraud.

-------------------------------------

Maximum jobs, not maximum profits.

uptick rule - Cramer, Bair

I watched Jim Cramer yesterday and Sheila Bair (God, she is just so much more impressive than Geithner! what can I say!)

Cramer has been pounding the drum to reinstate the uptick rule and I've heard there are "issues" with the technical, automatic trades and resolutions.

I don't believe that actually because one can make algorithms with time stamps in the nanoseconds and I'm sure those exist in the automatic trading desk...

in other words whatever technical issues there are with billions of trades and implementing a raising floor requirement, that should be doable in algorithms in the trade execution software so I don't get this technical issue argument.

But Cramer is pounding on derivatives ETFs like Proshares SKF which isn't tracking perfect to what they claim which is 2x the financial sector Dow Jones....but is also a place where shorts can load up way past what they can actually afford.

It's fairly clear that rumor and a few other things are ganging up on certain stocks but on the other hand...

who here thinks Citigroup, AIG, Bear Sterns, Lehman Brothers, BoA, JPMorgan Chase, etc. were solvent at the time?

I hope you write more into volatility and timing for that is one of the things I noticed in these meltdowns...

things happen so quickly have now amazingly fast slope due to the electronic trading systems....

a disaster can happen before a government administration can even get on the phone to do something or walk across his desk.

Sure volatility is good but is delta epsilon volatility good when we're dealing with human real world response times?

put call parity

What I don't understand about the love of short bans (with possible uptick rules) is that the market can still adjust and perform the same action. If I short a call and buy a put, I've in effect created a short on the stock, and yet it is legal. Unless that market is entirely regulated to stop people from selling/buying at will, this seems impossible to stop. Thoughts?

No, you hit the nail on the head there

There are other ways to short a stock or industry. One can, as you pointed out, short a call or buy a put if one is bearish on a stock. Some more "sophisitcated" traders also go one step further, and look for correlaries that take advantage of the situation. For example, one popular trade is to go long airline stocks if you think oil is going to fall, or go long the GDX (the gold mining stocks ETF) if you think gold will go up. Then there is shorting the futures contract, like the S&P 500 e-mini. A few years ago, the US saw the birth of a new product, Single-Stock Futures, traded on OneChicago Exchange (which is jointly owned by Interactive Brokers, the Chicago Board of Options Exchange, and the CME Group). Not exactly popular with the retail investment crowd, mainly institutional players use them. They're not a bad product actually. They tend to move at the same rate and near the same price as the original stock, but you only have to put down 20% of the value of the contract (which represents 100 shares). Like I said there are many ways to be bearish on something.

So with that being the case,

So with that being the case, it seems like the article attempts to convince that the uptick rule is valid, helps, and should be reinstated. If you don't need to actually short to perform a short, what good would reinstating the uptick rule do?