The Baldwin Piano Company was once the largest US-based manufacturer of pianos. The company can trace its origins back to 1857 by Dwight Hamilton Baldwin. By 1913, business had become brisk, with Baldwin exporting pianos to thirty-two countries. By 1953 the company had doubled production.

Throughout the 1970s, the company undertook a significant bid to diversify into financial services. Under the leadership of Morley P. Thompson, Baldwin bought dozens of firms and by the early 1980s owned over 200 savings and loan institutions, insurance companies and investment firms.

(Pictured below: The Baldwin Hamilton studio piano (model 246) was built in 1981 during a high point in the life of the Baldwin Piano Company.)

By 1982, the piano maker had turned itself into a financial powerhouse through its acquisitions. However, the piano business contributed to only three percent of Baldwin's $3.6 billion in revenues.

The company had taken on significant debt to finance its acquisitions and new facilities, and was finding it increasingly difficult to meet its loan obligations. The company portrayed their previous acquisitions as cash deals. So analysts had touted the stock and its value soared before the truth about its liabilities ever came out.

Class action lawsuits were filed against the company charging that it inflated the stock price by disguising the nature of its acquisitions, and by the end of 1983, Baldwin-United went bankrupt with a total debt of over $9 billion. At that time it was the largest U.S. bankruptcy ever. It was financial chicanery that led to the demise of Baldwin-United.

The Wall Street Journal wrote on September 5, 1985: Loosely Allied Traders Pick A Stock, Then Sow Doubt In an Effort to Depress It. "Wall Street's short sellers are worse than ambulance-chasing lawyers. Not only do they seek profit from others' misfortunes, but the critics say, a new breed of activist short sellers tries to help the bad news happen."

The Wall Street Journal front page story was about a network of short sellers, and was said to include a man named Jim Chanos. The story suggested that this network destroyed public companies for profit and described some of the more egregious tactics such as: espionage, impersonating journalists to get inside information, conspiring to cut off companies’ access to credit and spreading dubious information — and that they were employed by Jim Chanos and others in this network.

In 2003 Fox News contributor Karen Gibbs later wrote: "Among other things, the incident helped make the reputation of short-seller Jim Chanos, who was one of the first to forecast financial difficulties at Baldwin United. Jim Chanos had sounded one of the earliest warnings about Enron almost two decades later."

By 2005, short sales on NASDAQ hit a record high of 6.2 billion shares for the month ending March 15th. Defenders of short-selling had argued that corporate critics were trying to divert attention from their own internal problems. Moreover, they wanted to silence analysts who published critical research and discourage journalists from writing about the issues raised.

"One of the more disturbing aspects of this is, if they don't like what you say, then they'll use shareholder money to sue you for calling attention to their shortcomings," says Jim Chanos, the short-seller who BusinessWeek also said issued early warnings about Enron.

On April 10, 2006 the BusinessWeek article titled The Secret Lives Of Short-Sellers wrote "The rise of hedge funds and Indie Research raises new questions about a shadowy world. Short-selling has become much more prevalent. Hedge funds dedicated strictly to the technique, such as those run by famed short-seller James S. Chanos of Kynikos Associates LP had $603 million in assets as of 2001, that according to Hedge Funds Research.

On September 19, 2008 the New York Daily News reported: "Feds crack down on practice of naked short selling stocks during crisis. One master of the game is Jim Chanos. His New York-based Kynikos Associates ("kynikos" means cynic in ancient Greek) made a fortune betting that Enron stock was wildly overrated and Enron went bankrupt the year after Chanos put his money down."

A few days later on September 22, 2008 Jim Chanos himself wrote a story for the Wall Street Journal defending his trades titled Short Sellers Keep the Market Honest.

On February 12, 2009 Bloomberg News' headline read: E-Mails Show Chanos Saw Nonpublic Fairfax Research -- "Jim Chanos’s Kynikos Associates Ltd., a short seller of Fairfax Financial Holdings Ltd., learned of negative analyst research on that company before it was published, according to unsealed court documents. Jim Chanos and Steven Cohen of SAC Capital Advisors LLC and other hedge-fund managers were accused in 2006 by Fairfax of cooperating to drive down the firm’s shares through short sales, according to a complaint by Fairfax seeking $6 billion in damages. Toronto-based Fairfax owns U.S. and Canadian insurers. Chanos forwarded an e-mail about research by John Gwynn, an analyst with brokerage Morgan Keegan & Co, to rival SAC Capital, the documents show. Morgan Keegan fired Gwynn for telling clients before publication that he planned a negative report. Morgan Keegan and Gwynn were also sued. All defendants denied Fairfax’s claims. Fairfax filed that e-mail along with others provided by the defendants with a New Jersey state court to support its claims.

On March 19, 2009 Bloomberg News wrote: Naked Short Sales Hint Fraud in Bringing Down Lehman. "The biggest bankruptcy in history might have been avoided if Wall Street had been prevented from practicing one of its darkest arts." (Lehman Brothers was first founded in 1850 by Henry and Emanuel Lehman as an Alabama cotton trader.)

On May 16, 2006, May 7, 2009 and again on July 15, 2009, as a lobbyist, Jim Chanos gave congressional testimony regarding the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 and recommended drafting a special Private Investment Company statute, specifically tailored for SEC regulation of private investment funds.

Jim Chanos, in congressional testimony to then-Chairman of the Senate Finance Committee Chris Dodd, said: "I am honored to have this opportunity to testify on behalf of CPIC [a lobbying firm called the Coalition of Private Investment Companies] ...regulation must be based upon activities, not actors...venture capital funds are an important source of funding for start-up companies or turnaround ventures. Other private equity funds provide growth capital to established small-sized companies, while still others pursue “buyout” strategies by investing in under-performing companies and providing them with capital and/or making organizational changes to improve results...private investment companies and their advisers are not required to register with the SEC if they comply with the conditions of certain exemptions from registration under the Investment Company Act of 1940 and the Investment Advisers Act of 1940...for policy makers who believe private investment companies and their managers should be subject to greater federal oversight...I would argue that simply eliminating the exemptions in either or both of these statutes will prove unsatisfactory....neither the Investment Company Act nor the Advisers Act is the right tool for the job of regulating hedge funds and other private investment companies."

On July 1, 2009 Deep Capture published a 15-part series (an exposé) saying, "Emails acquired by Deep Capture show that hedge fund manager Jim Chanos, among others in his network, received and traded ahead of biased reports published by a research outfit called Morgan Keegan. After Deep Capture reporter Judd Bagley broke this story, the SEC began an investigation into the matter.

Evidently, back in the 1980s (during the time of the Baldwin Piano Company) Gilford Securities had once employed Jim Chanos, who now manages a few hedge funds, the most famous of which is called Kynikos Associates. He is also the head of the short seller lobby in Washington (CPIC), and a much favored source of information for the New York financial press.

In 1985 – back when Chanos was still at Gilford Securities; when journalists used to do investigations, rather than parrot whatever Jim Chanos whispered in their ears — was when The Wall Street Journal published a front page story about a “network” of short sellers, said to include Jim Chanos and Michael Steinhardt.

That was the story that suggested that this network destroyed public companies for profit and described some of the more egregious tactics: espionage, impersonating journalists to get inside information, conspiring to cut off companies’ access to credit and spreading dubious information — employed by Chanos and those in his network.

At the time, Chanos had been making some effort to publicly distance himself from Michael Milken (famous for junk bonds). And Chanos told one reporter that lawyers threatened him in the 1980s because he was selling short companies that had been financed by Milken’s junk bonds. However, the truth is that Chanos’s short selling in the 1980s tended to support Milken’s machinations, and in later years Chanos remained very much a part of the old Milken network.

Chanos had got his big break in the 1980s by short selling and ultimately destroying the piano company called Baldwin United. As part of this effort, Chanos and his colleagues at Gilford Securities went so far as to meet with Baldwin United’s bankers, and convinced the bankers to cut off Baldwin’s access to credit. Soon enough, the company went bankrupt, and Michael Milken quickly got himself hired as advisor to the bankruptcy.

According to a well-known businessman who was involved in the bankruptcy proceedings, Milken abused his advisory position, handing out confidential information to his network, which ended up owning much of Baldwin’s assets.

As the story goes, Chanos’s take down of Baldwin impressed Michael Steinhardt (the short-seller whose father was described as the “biggest Mafia fence in America”), so Steinhardt introduced Chanos to his key limited partners – including Ivan Boesky (later indicted for manipulating stocks with Milken) and Marty Peretz (a Milken and Boesky crony who would later co-found the website TheStreet.Com), along with Boesky crony CNBC's Jim Cramer - and a few hedge funds in this network.

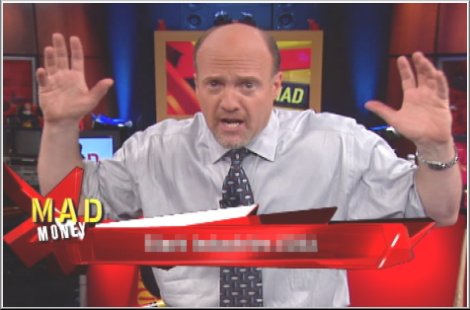

(Pictured below: CNBC's stock guru Jim Cramer of Mad Money and co-founder of the website Street.Com)

Marty Peretz, an aristocrat who has long been a part-time professor at Harvard, introduced Jim Chanos to one of his former students, Dirk Ziff (net worth $4 billion on the Forbes List) who manages a hedge fund called Ziff Brothers Investments. The emails previously cited show that the Ziff Brothers, just like Jim Chanos and Steve Cohen, were receiving advance copies of those Morgan Keegan reports.

Dirk Ziff is part of the same network. Jim Chanos launched his first hedge fund out of Dirk Ziff’s offices. This was a few years after Chanos left his position at Gilford Securities, which had a few key clients, one of whom was Michael Steinhardt, son of “the biggest Mafia fence in America.”

In the 1990s, five Gilford Securities traders — Chester Chicosky, Todd M. Nejaime, Lawrence Choiniere, Kevin P. Radigan, and William P. Burke — were arrested as part of "Operation Uptick", the biggest Mafia bust in FBI history. Although some of these traders had left Gilford Securities by the time they were indicted, they were charged with crimes allegedly committed while they were still working for Gilford. Specifically, the Gilford traders were charged with accepting bribes from a Mob-run brokerage called DMN Capital, and for helping to manipulate stocks with a cast of characters that included ten Mafia soldiers and a former New York police detective.

H. Robert Holmes, who was Jim Chanos’s boss at Gilford Securities, was asked whether he had any comment on the Mafia’s infiltration of his firm. He said, “I don’t know what you’re talking about...this is bullshit.” He also said he was completely unaware that any Gilford traders had been arrested for accepting bribes and manipulating stocks with a large cast of Mafia goons and Mafia associates. That is, he claimed to be unaware of an event in his company that had been vigorously publicized by the FBI and the SEC.

By the time of the FBI's "Operation Uptick", of course, Chanos was no longer with Gilford Securities. He was then a “prominent investor” – a member of the world’s most powerful network of financial operators, a network whose members are portrayed by the press as geniuses and heroes, never mind that this is the very network that has been destroying companies since 1980s — the very network that is (as should now be apparent) comprised of the criminal mastermind Michael Milken and his Mafia-connected cronies.

As a member of this network, Chanos is, of course, on close terms with Jim Cramer, the CNBC personality who once planned to run his hedge fund out of Milken co-conspirator Ivan Boesky’s offices. It was owing to Cramer that Chanos became the largest donor to the political campaigns of New York Governor Eliot Spitzer, who was Cramer’s best friend and former college roommate.

When Eliot Spitzer was caught with a hooker and forced to resign, it emerged that the hooker, Ashley Dupre, had been living rent-free in Chanos’s beachside villa. Ashley called Jim Chanos “Uncle Jim.”

(Pictured below: Jim Chanos (“Uncle Jim”), Ashley Dupré (posing for Playboy), and the former New York Governor Eliot Spitzer.)

These relationships bind some particularly destructive short sellers and miscreants. It is this network that shorted the big banks and helped trigger the collapse of the financial system. And members of this network are now the most “prominent” players in the biotech space.

One of those players is Jonathan Aschoff, the doctor-impersonating fraud who was, in the Spring of 2007, making the long-shot prediction that the FDA would not approve Dendreon Corp's “dangerous” treatment for prostate cancer. As we know, Aschoff previously worked for Sturza’s Institutional Research, run by a fellow who faced multiple SEC investigations (none of which led to any action) for allegedly publishing false information to help short sellers (such as Michael Steinhardt) manipulate stocks.

Under the strain of those investigations, Evan Sturza shut his operation down. Now Sturza helps manage a hedge fund called Ursus, which is owned by Jim Chanos, the Steinhardt protégé who housed the hooker of Cramer’s former college roommate, Governor Eliot Spitzer.

Ursus specializes in shorting biotech stocks. There are Wall Street brokers who say that Ursus was short selling Dendreon Corp while Sturza’s disciple, Jonathan Aschoff, was bashing the company and others in this network who were looking to cash in.

But it is difficult to know for sure whether Ursus was selling short. It is difficult to know who was responsible for flooding the market with at least 9 million (and maybe tens of millions of) phantom Dendreon shares. It is difficult to know because the SEC did not require hedge funds to disclose their short positions, and does not release information on who is selling stock and failing to deliver it. As far as the SEC is concerned, it’s all a big secret.

Can you imagine what a fund like the Vanguard Group could do, the nation's largest private equity fund with over $1.7 trillion in assets?

Forbes reported on April 8, 2009 that Jim Chanos is on the list for Wall Street's Highest Earners. "Short-seller James Chanos, who famously predicted Enron's collapse, also made the list for the first time, ranking ninth with a $300 million paycheck. Ursus Fund (Ursus Partners, as well as Ursus International) Chanos' flagship, was up an estimated 48% net of fees, compared with 25% for the average short-selling hedge fund, according to Hennessee Group, a hedge fund data tracker.

On March 31, 2011, in a letter to the SEC, Jim Chanos writes: "In view of the volume of information that will be newly required of the largest private funds [re: Dodd-Frank], we believe the commission [SEC] will need to develop a workable, flexible reporting schedule, particularly for initial reports. We also urge the commission to take all steps necessary to protect the confidential proprietary information filed by private funds with the commission under its proposed rules."

Once a week, investment managers with at least $100 million under management must report their daily short positions to the SEC. Some hedge funds that specialize in short selling were not happy about this new rule.

In a Fox Business interview Jim Chanos said: "Such a requirement is akin to the government suddenly requiring Coca-Cola to disclose their secret formula for free to all their competitors." Chanos attacked the new rules as "hasty" and "ill-considered" and went on to say that these rules "could be extremely harmful to the capital markets."

Eric Tyson writes, "James Chanos argued for continued non-disclosure of short selling practices and holdings. His 'trade organization' is a powerful lobbying company in Washington D.C. which Chanos failed to disclose. Chanos was all too willing to go onto CNBC for extended interviews where he was lobbed softball questions about his short selling strategies and where he got great public relations for his fund."

On October 12, 2011 Business Week wrote: "Demonstrators in New York had marched to the upscale Upper East Side neighborhood as the Occupy Wall Street movement that started in New York’s financial district spread to other U.S. cities. Jim Chanos, founder of the $6 billion hedge fund Kynikos Associates, and Bill Gross, who runs the world’s biggest bond fund, joined top asset managers in voicing understanding for anti-Wall Street protests as they spread to Manhattan’s Upper East Side, home to the city’s financiers. "People are angry, they feel the game is rigged, that they didn’t get their fair shake,” he said.

I almost laughed out loud when I read that.

On October 17, 2011 in an interview for Market Watch James Chanos warned, "Western investors must remember that Chinese consumers are not the next big hope,” and during the interview, he briefly revisited another reoccurring theme. “Corruption is endemic there. Contracts are meaningless."

On February 16, 2012 CNN Money wrote: "Is China faking its economic growth? Influential short-seller Jim Chanos thinks so. Known for predicting the Enron collapse, the chief of Manhattan-based Kynikos Associates, has been betting on a Chinese slowdown for a few years now, and once famously remarked, the world's second largest economy is on a 'treadmill to hell.' Jim Chanos thinks the Chinese government is understating its inflation problem -- thereby making its economy look stronger than it actually is."

He told CNN Money's Poppy Harlow in the interview, "One of the things I'm pretty convinced of, based on our analysis, is that inflation is under-reported in China."

In March 2012 an intriguing anecdote was reported in the New York Times, which was taken from the book “The Partnership: The Making of Goldman Sachs” written by Charles D. Ellis and published in 2008.

The story (below) is told by John S. Weinberg, who was then a young Goldman Sachs banker. 25 years later he became the vice chairman of Goldman Sachs. (His father Sidney. J. Weinberg also once ran the firm.)

After making a lot of money going public with his own company, a corporate raider noticed that Baldwin United was selling at a very cheap price. So he took a big position and was going to offer to buy the rest of the stock at a price well above the market. Since the founding family’s stock was held in a trust at a bank, the raider knew the bank trustee would be under terrific pressure to accept such an offer and sell the stock.

Takeover defense is something Goldman Sachs specialized in, so we were asked to help. After a study of the situation, it’s clear: They’ve got a real problem. I have no great ideas about what to do to help, so I ask Pop for suggestions. At first, he’s not sure either. A little later, he calls me on the phone and tells me to call a particular guy, and when I do, the guy tells me to meet him at the Gage & Tollner restaurant in Brooklyn.

I’m sitting there when this fellow wearing a black suit, black shirt, and a black string tie comes in and sits down, saying, “The only reason I’m here is I owe your father.”

I explain what I know, and he says he’ll see what he can do. I don’t hear from him for a week, then two weeks. Finally, he calls and says, “We’ve got him. It’ll cost a hundred dollars — fifty dollars for the photographer and fifty dollars for the bellboy. He’s got a cutie holed up in a midtown hotel.”

A week later this same guy calls on the corporate raider and very respectfully says to him, “You believe in this free country, and so do I. Anybody can buy anything in this wonderful free economy.”

Then he starts spreading the pictures from the hotel on this man’s desk, and says, “You can buy almost anything. But don’t do Baldwin or these could show up in The New York Post."

Nothing happened to Baldwin United, and nothing was printed in the newspapers.

This blogger had been wondering who that "corporate raider" was, and that's why I researched this article. But who was the guy in the black suit?

Today, between the opulence of Fifth Avenue's shops and the grandeur of Sixth Avenue's corporate row is the epitome of boutique office buildings called The Tower at 20 West 55th Street. It was conceptualized in the early 1980's as the United States Headquarters for a European bank. The Tower is among Manhattan's most distinguished office complexes. Combined by a dramatic eight-story atrium, the elegant limestone townhouses and the modern fourteen-story tower, blend nineteenth century elegance with the sophistication of a modern business environment.

It's here where you might find Jim Chanos, sitting behind his desk in a penthouse suite on the top floor, plying his trade...shorting stocks.

(Pictured below: The Tower and the rear balcony at 20 West 55th Street in midtown Manhattan, New York City.)

Comments

Great title

I had no idea on the history of Baldwin pianos, great piece! And we thought we were just practicing the notes, who knew others were learning how to short a stock to oblivion.

Hack Job

Fundamental short selling helps find the proper stock price in a world of stock promoters. It is not clear from your article that Baldwin-United was primarily an insurance company. Chanos made his name, and landed in a front page article in the Wall Street Journal, by finding things to object to in their accounting.

As soon as I read 'naked short selling' in your article, I knew that the rest was nonsense. Naked short selling is a red herring. It is rare, and has little impact on the markets.

No Hack Zone

Well for one thing, it seems that whether or not Baldwin-United eventually became primarily an insurance company is irreverent. As far as “naked short selling” being “a red herring”, “rare” and having “little impact on the markets” -- that is a very debated subject. There were proposed rule changes by the SEC to limit short-selling during the crash of 2008/09. And the article wasn’t primarily about “short-selling” specifically, but about all of the manipulation in the markets in general. All the info I provided was gleaned from other article with links, so you can debate the merits of those sources with them. Overall, I thought the story was interesting nonetheless. If you want to add a “correction”, I think you should. But I’m not sure how I could edit it to make it more “accurate”. Thanks for commenting.