Events of the past two years have made food an increasingly worrisome item in household budgets and in the budgets of nations. In early 2008, food prices to the American consumer were 25 percent greater than two years earlier. This reflected dramatic increases in farm beef prices, while farm corn prices were double and wheat prices triple those of early 2006. Clearly something new has happened to a food market which has historically fed Americans well and for a uniquely small proportion of their income.

A series of events was associated with these price adjustments. In 2005 the U.S. dollar began to depreciate and a major realignment of international currencies set underway. (1) [A series of crop failures and poor harvests around the world magnified the food problem]. Finally, Congress adopted legislation that drastically altered the framework of American agriculture....

- Foreign Affairs (2)

Add to this a "guns 'n' butter" fiscal policy of protracted war without either budget cutbacks or raising taxes to pay for it, and the recipe for World Food Crisis was created.

(Note: I quote extensively from open access free research in this diary. Other, copyrighted material has been chopped to a bare minimum to comply with fair usage. Links are footnoted and provided at the end of the diary ).

In order to understand the origins of the World Food Crisis, one must first go back to those reckless fiscal policies of budget and trade deficits, and of running wars without paying for them. As Time Magazine reported (3), the resulting

international monetary crisis was certainly the worst since World War II. Even so, its true gravity could not be gauged by those factors alone. ... the upheaval at first seemed artificial and contrived. But it quickly became a pointed revolt against the U.S. dollar, the foundation stone of the whole system of Western finance. For the first time, much of the world, in effect, was asking about the dollar the question that arrogant American tourists sometimes ask about other currencies: "How much is that worth in real money?".... Once the speculation began, it turned into a stampede away from the dollar, and toward not only the Euro but every other strong currency in sight (4)

....

Decades of U.S. balance of payments deficits [ ] have poured more dollars into foreign nations than the dwindling Treasury ...can cover. .... [T]he dollar has become an international paper currency, backed only by the competitive strength of the U.S. economy.

....

That change in status has had a profound effect upon the psychology of the world's financiers, businessmen and government officials, who no longer regard the dollar with awe....(5) As the supply of dollars in foreign countries begins to exceed the demand, the price of the dollar in those nations begins to drop. Consequently, the price of the foreign currency, in terms of dollars, rises. In order to prevent prices from fluctuating more than the rules of the system allow, foreign central banks must then buy up the surplus dollars with their own currencies.After a spell of worry about the balance of payments in the 1990s, Washington's attitude [ ] settled into smug nonpartisan complacency... . Government officials have taken the line that any foreign nation unhappy about absorbing dollars can simply increase the official value of its own currency, ... thus relieving itself of having to buy up quite so many dollars.

Fortunately, a very good scholarly overview by the International Food Policy Research Institute has been published: (6)

EVENTS LEADING TO THE CURRENT SITUATION

The world in general, and Americans especially, had grown complacent about their food supplies in the 1990s....

Indeed, until the early 2000s the world food situation did appear well in hand. World production of grains, the foundation of the food supply for most of the world's population, rose almost every year from 1994 through 2006. The world output grew steadily despite large-scale production control programs in the United States.

As you may already know, feed grain is the ultimate food source of almost all food. While grains may be eaten directly in poorer countries, with meat, poultry, and fish added; in developed nations, the grains are fed to meat and dairy animals which in turn provide meat, poultry, and dairy products for rich consumers.

As the International Food Policy Research Institute policy paper describes, "Two factors affect the demand for grains-population growth and income growth":

The world's population is about 6 billion people at present, Nearly three-fourths of these people live in the developing countries and over half of them in Asia.... The population growth rate in the developing world is about 2.5 percent per year; in the developed world about 0.8 percent. Thus, each year there are 120 million more people to feed, over 105 million of them in the developing countries..... For the world to sustain its consumption patterns of the beginning of the decade about 30 million tons annual increase in output is required.

There are other factors. Generally, there has been a slow but steady growth in per capita income and with it a rise in the demand for food. In the poor countries, and among the poorest in all countries, the income elasticity of demand for food is high. Thus, increased affluence adds to the demand for grains. As poor people grow wealthier, they increasingly shift to more meat, dairy, and poultry products. A modest rise of income

together with population growth will call for an increase of nearly 3 percent per year in food output to keep up with demand without sharp increases in prices. And, a 3 percent increase annually means food production must ... double every 23 years! Finally, the demand for food is highly inelastic-meaning that it responds very little to changes in price. To put it another way, small changes in availability will cause large changes in prices, as we have seen in the past few years.

Similar facts are highlighted by a International Relations and Security Network paper (7) describing the "complex and multi-causal" nature of the Crisis:

Three long-term trends have collided with a series of short-term events to produce a dangerous situation ....

The first trend is that most countries have not yet started to go through a demographic transition, yet many are experiencing population growth-rates of 3 percent per year or above. Moreover, such countries typically have a large proportion of their population under the age of 14 - a category that clearly cannot contribute much to food production but had high nutritional needs.

The second long-term trend is the relative neglect of rural development throughout the 1980s and 1990s, when most development emphasis is on urbanization and industrialization, in an effort to transform the lives of the great majority of people in the "third world" who live off the land.

The third trend is that economic growth in industrialized states in the 1990s resulted in a move towards more meat-rich diets, with all the inefficiencies of ecological conversion rates that this involved - typically ten kilos of plant protein to produce one kilo of animal protein.

.... In addition, the crisis has four immediate causes: (8)

Poor weather conditions in many parts of the world....

A substantial increase in fertiliser prices....

A huge increase in oil prices....

The partial failure of the green revolution. Many of the new miracle-plant varieties are indeed remarkable, but they depend on the ability of the farmers growing them to afford the fertilizers, pesticides and adequate irrigation that they so often require. When prices of fuel and fertilizer are high, the miracle-plant varieties are starved of precisely those inputs needed to maximize yields.

As to the inefficiency of using grain to create meat diets, a second, lengthy feature article in Time Magazine (9) said:

The industrial world's way of eating is an extremely inefficient use of resources. For every pound of beef consumed, a steer has gobbled up 20 Ibs. of grain. Harvard Nutritionist Jean Mayer notes that "the same amount of food that is feeding 315 million Americans would feed 2.25 billion Chinese on an average Chinese diet."

True, there may have been a substantial amount of malnutrition in some developing countries, but global agricultural production growth and global consumption of food grew in rough equilibrium until 2004. As described by the International Food Policy Research Institute, the loss of balance was further exacerbated in 2006 by crop failures or cutbacks due to changed weather conditions in such diverse places as in Russia, Asia, and Africa. (10) Instead of adding 30-36 million tons of grain that year, global food output dropped for the first time in 20 years, by about 45 million tons.

So much bad weather started to plague so much of the world's crop land that many experts conclude that it was proof of global climate change. (11)

The production shortfalls, global climate issues, population growth and changes in diet due to affluence all acted together to bring the World Food Crisis to a head: (12)

.... By the beginning of 2007 (13), grain stocks were down to 10 percent of annual consumption, and prices began to rise, sharply in the United States and wildly in some of the food-deficit developing countries.

.... By 2008, grain prices were at record levels.... The developing countries, buffeted by high fuel prices, fertilizer shortages, and inadequate grain supplies, were frightened and rightfully so ....

The devastating results finally became apparent: (14)

[I]n 2007, [ ] a new set of problems threatened food output, especially in the underdeveloped countries. Fertilizer was in short supply, and its price started to climb. Then came the devastating impact of the quadrupling of the market price of petroleum by the cartel of oil-possessing nations. Higher oil prices meant added costs for the farmer: pesticides, herbicides and nitrogen-based fertilizers are derived from petroleum, while the manufacture of all fertilizer requires much energy. The world price of nitrogen fertilizer more than doubled in the last 2 years .... (15)

....

in the past two years, ... hunger and famine began ravaging hundreds of millions of the poorest citizens in at least 40 nations... , and experts now question whether man can prevent widespread starvation.The world's reserves* of grain have reached a 22-year low, equal to about 26 days' supply, compared with a 95-day supply in 1995, [and some nations which normally export food, such as China and Thailand, have halted exports in an effort to stabilize their own internal food supplies]. ...

Nearly half a billion people are suffering from some form of hunger; 15.000 of them die of starvation each week in Africa, Asia and Latin America. There are all too familiar severe shortages of food in the sub-Saharan Sahelian countries.... In Haiti, because of disregard for soil conservation, .... Whole families are often so hungry that they do not wait for mangoes to ripen; they boil the green fruit and eat it [and have been reported as reduced to eating mud] .....

Food riots have become commonplace in vast sections of the third world. (16)

One magazine cover seems to exemplify the stark reality of the World Food Crisis:

What about the Future?

The alternatives as set forth by the International Food Policy Research Institute seem stark:

As we look ahead, the task of feeding the world is a formidable one! ..... Most of the easy gains are gone, especially in Asia, where the problems loom largest. Most of the available land suitable for crop cultivation is being used; in fact, farming on land that is too dry and too steep threatens irreversible ecological damage in some areas. Despite high fuel and fertilizer prices, most of the expanded output must come from higher output per area of land. This means more irrigation, better varieties, more intensive cultivation, and better farming practices. Behind this there must be research, investment, education, and the mobilization of national and international will. The margin of safety is too narrow and the price too high to allow our efforts to lag.

There is substantial disagreement on this subject. Some already have predicted widespread famine as inevitable in major areas of the world and have even talked about "triage,"... (17)

The dire warnings were echoed in the conclusion to the Time Magazine article:

This grim prognosis has led to apocalyptic warnings from some of the world's top food experts. "We will see increasing troubles, not declining troubles," predicts Dr. John Knowles, president of the Rockefeller Foundation. "We will see increasing famine, pestilence, the extermination of large numbers of people. Malthus has already been proved correct." The most vulnerable to such disasters: India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, the Sahel nations, Ethiopia, northeast Brazil, the high regions of the Andes and the poor parts of Mexico and Central America.

This deteriorating situation poses a dilemma for the wealthy, food-surfeited citizen of the developed world. He must decide whether he has a moral obligation to feed those who are starving even if the food shortage in the poorest countries could have been prevented by population control. Morals aside, out of sheer self-interest he must ponder whether the hungry half-billion will allow him to live peacefully, enjoying his wealth. (18)

But there is hope also:

On the other side are those who view the recent situation as only temporary. They believe that technology is adequate and that it will be adopted through the normal pull of market forces. .... However, given what is known and not yet applied, and prospects for future research developments, there is no reason that the world cannot meet its food requirements for at least the next decade. The determinant is likely to be the

political will, both in developing and developed countries, to make the hard policy choices to encourage the necessary production and equitable distribution of food. (19)

In Conclusion, History may not Repeat, but it does Rhyme.

And now, I must make a small confession. I made slight changes in the quoted material above. All of the dates have been moved forward 34 years. The time period described isn't 2005-2008, but 1971-1974. Similarly, decades have been moved forward 30 years (e.g., 1990s for 1960s). To cope with population growth, those numbers have been increased by 50%. Very slight emendations have been made (where you saw footnotes) and the changes have been listed below.

Aside from that, everything is a verbatim quote from the World Food Crisis of the early 1970s. The articles could have been written today, though, couldn't they have? The war (Iraq/Afghanistan vs. Vietnam), the dollar collapse, the population increases, the weather changes, the changes in diet, all are as spot on now as they were then.

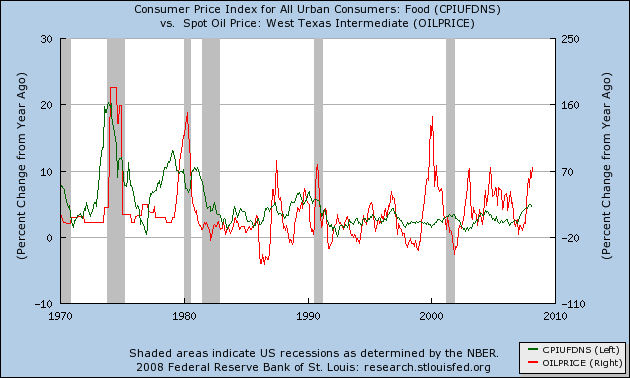

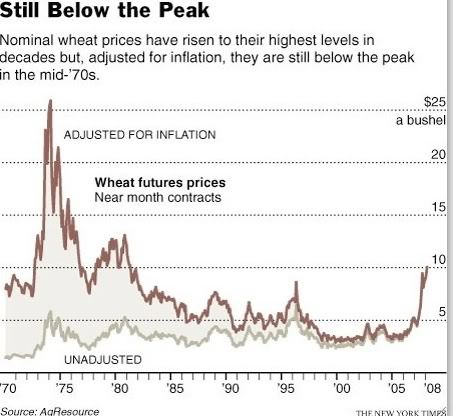

And as bad as today is, actually it hasn't yet approached the impact of the early 1970s crisis. Here's two graphs, first of food (in green) and energy (in red) inflation beginning in 1970, and secondly in the real, inflation-adjusted price of wheat since then:

As you can see, we are indeed well "below the peak" of the real cost of food and inflation that occurred in the early 1970s. Imagine the current cost of rice, wheat, and meat doubled again from here and you begin to see how dire the situation was.

Back then, in late 1974, a "World Food Conference" was convened, the world's leaders attended, and the US was deeply involved in supplying grain (imperfectly, mainly to its third world allies in the Cold War) to the developing world. The "World Food Program" agency that you are reading about now in the news, was created then.

The odds of the Bush malAdministration taking the lead, that even the Nixon Administration did, appear vanishingly small. Whoever the next, hopefully Democratic, President is, he or she will have yet another crisis that was in substantial part aided and abetted by disastrous fiscal and pork-laden farm policies of Bush and the GOP Congress, on their plate.

______________________________

Links and emendations:

(1). -was floated- [began to depreciate]

(2). Foreign Affairs

(3). Time Magazine, May 17, 1971

(4). -mark- [Euro]

(5). -European- [the world's]

(6). International Food Policy Research Institute (free access publication)

(7). International Relations and Security Network (ISN) (creative commons license) (past tense changed to present tense).

(8). -of 1973-74 had- [has]

(9). Time Magazine, Nov. 11, 1974

(10). -the Soviet Union- [Russia]

(11). Time, Nov. 11, 1974

(12). International Food Policy paper.

(13). -the time of the World Food Conference- [2008]

(14). Time, Nov. 11, 1974

(15). -jumped from 11¢ per Ib. in 1972 to 25¢ now- [more than doubled in the last 2 years]....

(16). -Bangladesh and India- [the third world]

(17). International Food Policy paper.

(18). Time, Nov. 11, 1974

(19). International Food Policy paper.

Comments

This diary is best understood as Part 3 of

the series that includes "Peak Everything?!?" and "China's out of control Inflationary Boom", dealing with the causes and historical precedent for today's commodity inflation and food and energy crises.