Discussing La Caisse's 2025 Results With Their Head of Liquid Markets

Nicolas Van Praet of the Globe and Mail reports Caisse posts 9.3% return in 2025 on gains from stock holdings:

Nicolas Van Praet of the Globe and Mail reports Caisse posts 9.3% return in 2025 on gains from stock holdings:Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec tallied an 9.3-per-cent return last year as gains from stock holdings offset a neutral performance by real estate investments in an environment marked by ongoing trade strife, global conflict and the expansion of artificial intelligence across society.

Net assets stood at $517-billion at the end of 2025, up from $473-billion the year before, the Montreal-based pension fund manager said in a statement Wednesday. The annualized return over five years was 6.5 per cent.

“It’s really a new world order out there,” Caisse Chief Executive Charles Emond said in an interview, noting the power of AI-related themes over stock markets among other major shifts taking place. Investment diversification remains the key to delivering stable returns as the uncertainty persists, he said.

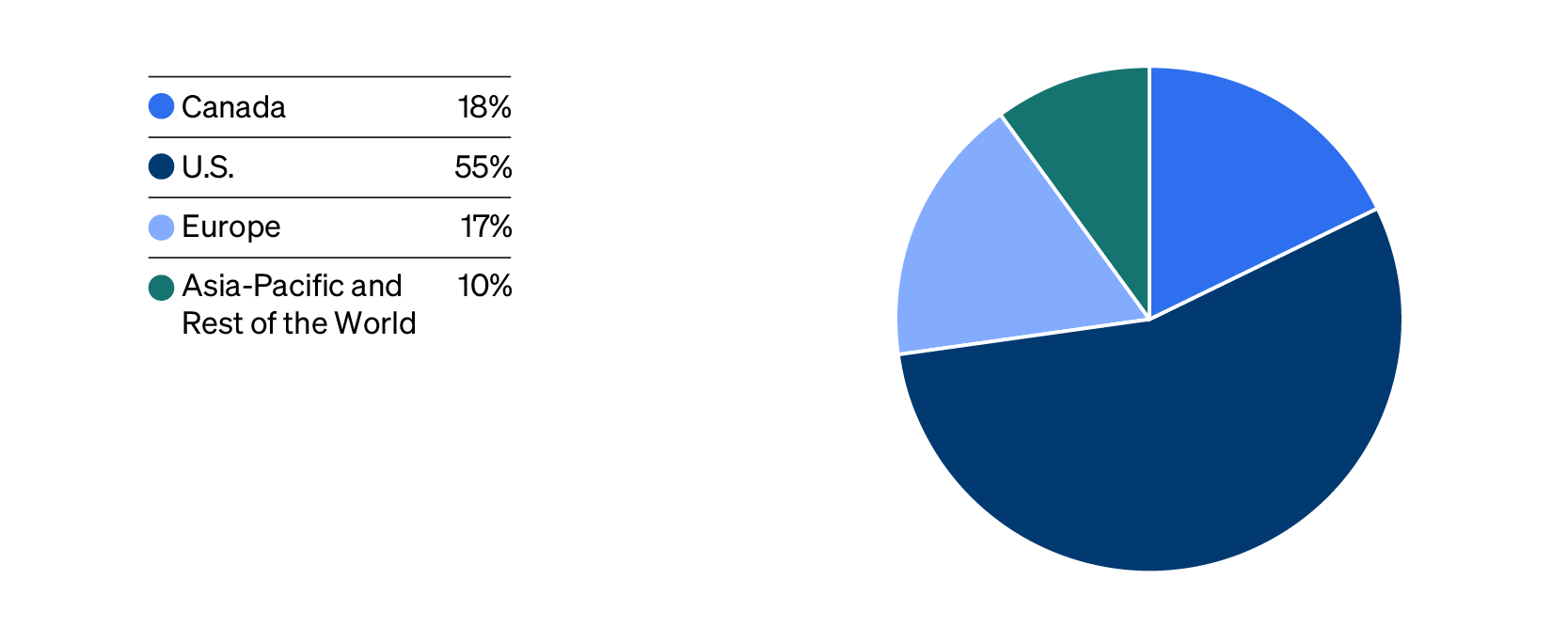

“The main risk we’re dealing with – and I would have never thought I’d say that during my career – is the U.S.,” Mr. Emond said. U.S. exceptionalism is still there, but it has eroded lately and “the level of trust” has been put to the test, he said. “It’s actually paid off to be invested elsewhere.”

The U.S. remains the deepest, most liquid and most attractive market for investors and the Caisse is not exiting the country, Mr. Emond insisted. But it is being more prudent in the way it invests there.

The pension fund pared back U.S. stock holdings last year while boosting credit activity. It also sold some U.S. office buildings while hedging more than usual on its U.S. dollar exposure. Roughly 40 per cent of its total assets are invested across the border.

The pension fund’s gain on equity market investments was 17.7 per cent for the year, the third best over the past decade, as it added to positions in other markets such as Europe and South Korea. Its infrastructure portfolio generated a 9.2-per-cent showing, driven by energy, ports and highway investments, while fixed income returned 6.6 per cent.

On the other end of the spectrum, the Caisse’s real estate holdings remained under pressure, delivering a 0.2-per-cent return as the market recovers. Private equity, usually a strong motor for the pension fund, generated a 2.3-per-cent gain as profit growth slowed for its portfolio companies and valuation multiples dropped in the technology and health care sectors.

The mixed results, which closely matched the previous year’s 9.4-per-cent return, highlight the magnitude of the challenges for Mr. Emond, a former Bank of Nova Scotia executive who took over as Caisse CEO in early 2020.

His tenure, which was recently extended to 2029, has been fraught with turmoil from the COVID-19 pandemic, record inflation, and wars in Ukraine and the Middle East. Donald Trump’s reclaiming of the White House has presented a new test: The President’s unpredictability has repercussions for trade and on the decisions of central bankers and corporate leaders.

The Caisse, which is independently run at arm’s length from the Quebec government, has a dual mandate to manage deposits with a view to achieving optimal returns while contributing to Quebec’s economic development. It is omnipresent in the province, investing in companies such as Alimentation Couche-Tard Inc. and WSP Inc. and pushing into transit development with Montreal’s $8-billion Réseau express métropolitain light-rail system.

Quebec Premier François Legault said last November that the Caisse “needs to do even more” to back local projects and business in the face of Mr. Trump’s trade war against Canada, which has hurt aluminum makers and forestry companies in the province. “I think the situation is critical right now,” the Premier said at the time.

The Caisse now has assets in Quebec topping $100-billion, a target it set three years ago. It hasn’t set a new goal, vowing instead to be “more intentional” on the impact of future investments in strategic sectors such as natural resources, defence and energy, Caisse executive vice-president Kim Thomassin told reporters at a news conference.

Among its biggest domestic deals in the past 12 months, the Caisse bought Innergex Renewable Energy Inc. for about $2.8-billion and struck a $1.3-billion deal with Telus Corp. for a minority stake in a new cellphone tower spinout called Terrion. It also made a US$100-million equity investment in Champion Iron Ltd to support the miner’s acquisition of Norway’s Rana Gruber SA.

Earlier this month, the pension fund briefly suspended its deal-making with DP World Ltd. in the wake of revelations linking the chairman and chief executive of the logistics multinational to disgraced financier Jeffrey Epstein. It has since resumed working with its long-standing partner after the executive resigned.

The only thing I will mention about this Epstein thing is the head of global ports operator DP World has left the company after mounting pressure over his links to convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein.

The Caisse briefly suspended its operations after discovering this and has since resumed them. Obviously they had no idea Sultan Ahmed bin Sulayem exchanged hundreds of emails with Epstein.

Anyway, today is a very big day because La Caisse posted its results and despite weakness in private equity and ongoing issues in real estate, they were solid powered by public equities, credit and infrastructure. Its Quebec portfolio also did well.

Now, this morning I virtually assisted the press conference from the comforts of my home and took a quick image of Charles Emond, Kim Thomassin and Vincent Delisle (at top of this post).

I must admit, that was the first time I virtually assisted this press conference and to my surprise, I thoroughly enjoyed it, thought Charles, Kim and Vincent did a great job and the slides which you will see below gave a perfect overview.

Typically I find these press conferences dreadfully boring and tiresome but this one was very well done, and for the most part, reporters asked decent questions and I told Charles, Kim and Vincent afterwards that they should post it publicly on their YouTube channel.

I'm not kidding, it was that good and if I was able to embed it, it would save me a lot of time explaining things.

One of the most important questions Charles tackled was why their underpeformance relative to benchmark over the last year (9.3% vs 10.9%) and whether it's worth investing in private markets.

Charles explained that they have a mandate from depositors to deliver returns taking risks into account and they have delivered strong gains over the long run by taking a diversified approach across public and private markets and this approach offers higher risk-adjusted returns.

I'm paraphrasing but if I get the transcript in French, I will post it here and I thought that was extremely well answered.

The only question I didn't like (it always irritates me) is how did La Caisse perform last year relative to its peers. Charles said their biggest client whose portfolio is closest to CPP Investments gained 9.8% last year which was better than CPP Investments' 7% return over last nice months and OMERS' 6% gain last year but we are comparing apples to oranges because the asset mixes aren't the same (CPP Investments and OMERS have more private market exposure).

There are so many factors that go into comparing returns across pension funds that I absolutely hate these questions and besides, they're all in great financial health, have way more assets than long-dated liabilities (and that's what ultimately counts, not outperforming each other).

One year those that have more public market exposure will fare better, another those that have more private market exposure will fare better. Who cares?

All of the Maple 8 funds underperformed Norway's sovereign wealth fund which gained 15.1% last year, it means absolutely nothing to me (all about asset mix!!).

Alright, let me get to this morning's press conference but before I do, some more articles in French:

- La Caisse à la traîne pour une troisième année d’affilée

- La Caisse annonce un rendement de 9,3 % en 2025

- Rendement de 9,3% pour la Caisse en 2025, sous la cible pour la troisième année consécutive

- La performance de La Caisse pour 2025 a été en deçà des attentes

Basically the French media is savage, La Caisse underperformed its benchmark for a third straight year, but overall performed well and beat OMERS (again, who cares?).

Morning Press Conference With Charles Emond, Kim Thomassin and Vincent Delisle

As mentioned above, I really liked this morning's press conference, so much so that I believe La Caisse should make it public and post it on YouTube as soon as possible (la transparence avant tout!).

Before I get to the slides, here is La Caisse's press release stating it posted a 9.3% return in 2025 and net assets of $517 billion:

- The depositor plans are in excellent financial health

- The base plan of the Québec Pension Plan, representing the pensions of more than six million Quebecers and the largest fund invested with La Caisse, earned a return of 9.8%

- The ambition of $100 billion invested in Québec achieved one year early

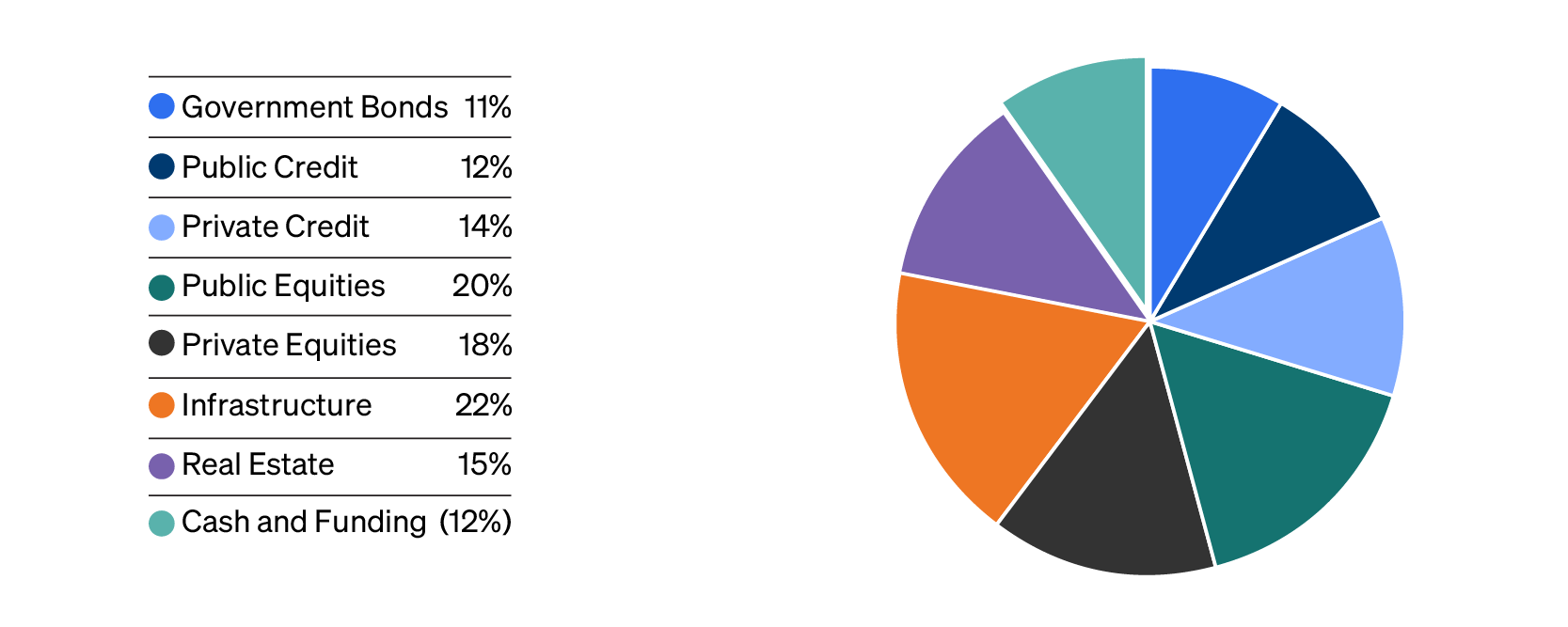

La Caisse today presented its financial results for the year ended December 31, 2025. The weighted average return on its 48 depositors’ funds was 9.3% for one year, below its benchmark portfolio’s 10.9% return. Over longer terms, performance is above the benchmark portfolio: over five years, the annualized return was 6.5%, with the benchmark portfolio at 6.2%; over ten years, it stood at 7.2%, against the benchmark portfolio’s 6.9%. As at December 31, 2025, La Caisse’s net assets totalled $517 billion.

In 2025, the environment was marked by geopolitical tensions and persistent tariff uncertainty. Nevertheless, the global economy proved resilient and stock markets once again posted a robust performance. Although central banks generally lowered their key rates, long-term bond yields moved in different directions, falling in the United States but rising in several other countries, including Canada.

“Last year, our overall portfolio posted a good return, with the right level of risk for our depositors. As public markets were particularly strong, they were the main driver of our annual performance. In an environment shaped by uncertainty and profound changes that are likely to persist, diversification remains essential, allowing each asset class to play its part across different market conditions,” said Charles Emond, President and Chief Executive Officer of La Caisse.

Return highlights“Looking back at the past five years, markets have been volatile and difficult to follow, with pronounced differences between asset classes and sharp fluctuations from one year to the next. Having stayed the course with numerous transactions in key sectors around the world, the advancement of structuring projects in Québec, and the rollout of a new climate strategy even against strong headwinds, all while maintaining the excellent financial health of our depositor plans, are all reasons to be proud of the role and impact of this major institution for Québec,” he added.

As at December 31, 2025, La Caisse’s investment results totalled $43 billion for one year, $134 billion over five years and $245 billion over ten years.

Forty-eight depositors with different objectives

La Caisse manages the funds of 48 depositors—mainly for pension and insurance plans. The overall portfolio’s one-year, five-year and ten-year returns represent the weighted average of these funds. To meet their objectives, investment strategies are adapted to individual depositor risk tolerances and investment policies, which differ considerably.

For one year, returns for La Caisse’s nine largest depositors’ funds ranged from 8.6% to 10.4%. Over longer periods, the annualized returns varied between 4.6% and 7.8% over five years, and between 5.8% and 8.0% over ten years.

The largest fund invested with La Caisse, the base plan of the Québec Pension Plan, administered by Retraite Québec, posted a return of 9.8% for one year, 7.8% over five years and 8.0% over ten years. As at December 31, 2025, its net assets were $163 billion, including the additional plan.

Equities

Equity Markets: Beneficial geographic diversification

Stock markets experienced a year of rotation in 2025, with the U.S. market being perceived as more uncertain, and giving up ground to other stock markets, such as those in Europe, Canada and emerging countries. The latter benefited from good performances in a variety of sectors, including technology, as well as materials and finance. Sound geographic diversification, combined with the quality of execution by portfolio managers, enabled the Equity Markets portfolio to record a return of 17.7%, its third-best performance in ten years, and to outperform the index in the vast majority of mandates. The benchmark index stands at 18.2%. The difference over the period is mainly due to the more limited contribution of certain Québec stocks in the portfolio, as well as its low exposure to the gold segment, which grew sharply during the year.

Over five years, the annualized return was 12.4%, above the 12.1% return of the benchmark portfolio. Performance therefore outpaced the benchmark index despite growing concentration of gains in the main stock market indexes during the period. The portfolio benefited from the 2021 changes aimed to take advantage of technology stocks. The launch of systematic management strategies, which leverage data processing capabilities using augmented intelligence, has also had a significant positive impact.

Private Equity: Slower growth affects portfolio

In 2025, the Private Equity portfolio posted a 2.3% return. This was the result of slowing earnings growth for portfolio companies and lower multiples in the technology and health care sectors. Some investments, although performing well since the initial investment, experienced a setback and weighed on performance during the year, despite the good performance of companies in the industrials sector. The benchmark index, half of which is made up of public stocks, returned 12.6%, as public markets were much more robust than the private market.

Over five years, the portfolio has been one of the main drivers of overall performance, boosted by investments in the industrial, financial and technology sectors, delivering an annualized return of 11.6%. Over the period, the more moderate performance of a handful of stocks explains the difference with the portfolio’s performance relative to its index, which stood at 14.7%.

Fixed incomeCredit activities are a strong vector of performance

The majority of the Fixed Income asset class is comprised of the Credit and Rates portfolios, with the latter serving as a source of liquidity for the overall portfolio. In 2025, the asset class generated a 6.6% return, above its benchmark index’s 4.6%. The Credit portfolio was a strong performance driver, with a return of 9.6%. It recorded its best ever performance against its index, which posted a 6.6% return, due to results obtained in the private segment, emerging market sovereign debt and the quality of execution by the teams.

Over five years, the asset class posted an annualized return of -0.2%, compared with a benchmark return of -1.1%. The good performance of the Credit portfolio over the period, driven by Capital Solutions and Corporate Credit activities, boosted the asset class, but failed to offset the impact from the strongest bond market correction in 50 years that occurred in 2022.

Real assetsInfrastructure: Consistent performance in diverse market environments

The portfolio has maintained its momentum of recent years, delivering a return of 9.2% in 2025. It benefited from an attractive current yield of 5.0% and the quality of portfolio assets. Energy, ports and highways were the largest contributors to performance. The benchmark index, made up entirely of public stocks, returned 13.4%. It was buoyed by the growth of companies in the electricity segment, which continues to be stimulated by the historic demand for artificial intelligence and weighs heavily in the index.

Over five years, the annualized return was 10.8%, outpacing the index’s 8.0% return. The portfolio continues to benefit from asset diversification, with the energy, transportation and telecommunications sectors leading the way, as well as from its strong current yield, across very different cycles over the period, marked in particular by higher inflation.

Real Estate: Progress on turnaround plan in an industry still under pressure

For one year, the portfolio posted a 0.2% return, compared with 1.8% for its benchmark index. In a gradually recovering market, direct portfolio assets in the logistics and residential sectors, as well as offices and shopping centres, posted a 4.4% return, a sign that rental incomes and property values are stabilizing. However, this return was offset by the high cost of financing. Lower performance of assets in China largely explains the difference with the index. It should be noted that the teams were particularly active in portfolio turnover, achieving a high transaction volume, totalling nearly $11 billion, or double the previous year’s figure.

Over five years, the portfolio’s annualized return was 1.2%, affected by its exposure to the office sector, which has been weakened by changes in working habits, but whose effects were mitigated by favourable performance in logistics. The benchmark index returned 1.4%, reflecting the challenges faced by the industry in recent years.

Global strategies that generate valueLa Caisse’s teams also employ global strategies to optimize performance, including positioning on macro factors and foreign currency management:

Québec: Ambition of $100 billion achieved ahead of schedule, with investments in local companies and impactful projects

- Macro tactical strategies contributed positively to overall portfolio performance in 2025, successfully navigating the volatility seen during the year, particularly in April with the unveiling of U.S. tariff policy, which prompted significant movement in global financial markets. These overlay activities, which are designed to improve the risk-return profile and enhance overall performance against the benchmark portfolio, have generated $1.2 billion in added value over one year.

- While the portfolio’s exposure to foreign currencies had an adverse impact on 2025’s overall performance due to the sharp depreciation of the U.S. dollar, the partial hedging of this currency put in place by the teams nevertheless protected $3.6 billion.

In 2025, La Caisse’s assets in Québec reached $100.1 billion. The organization deployed $6.3 billion in new investments and commitments during the year.

Among the teams’ accomplishments, we note:

Support to grow companies in key sectors

- Innergex: Privatization of this renewable energy leader, bringing the enterprise value to $10 billion

- Boralex: $200-million financing, doubling existing debt financing in this company of which La Caisse has been a major shareholder for nearly ten years

- Honco Group: Minority interest to consolidate Québec ownership of this steel processing specialist

- Ocean Group: Additional investment in the context of the shareholder structure evolution of this maritime industry leader in Québec and Canada, bringing La Caisse’s stake to $120 million

- Germain Hotels: Lead of a $160-million financing round to accelerate its expansion and support the company’s succession

Structuring projects: An edge for Québec

Climate: A new strategy for increased impact in all sectors of the economy

- REM: Commissioning of the Deux-Montagnes branch, tripling the network’s coverage, with 19 stations spanning 50 km

- TramCité: Announcement of the six consortia qualified for two major contracts in the request for expressions of interest process, an important step in the procurement process for this 19 km tramway project in Québec City

- Alto Québec City-Toronto high-speed train: Cadence team, led by CDPQ Infra, selected as private partner by the Government of Canada and contract signed with the project authority

- Terrion: Transaction worth close to $1.3 billion to create, with Telus, the largest specialized wireless tower operator in Québec and to establish the head office in Montréal

- Laurentian Bank: Support for the acquisition transaction by National Bank and Fairstone Bank, through guarantees obtained to maintain Laurentian Bank’s commercial head office and to relocate Fairstone Bank’s head office to Québec

- AI expertise: Launch and implementation of a program powered by Vooban to support company productivity in the face of tariff challenges; recruiting for a new cohort currently underway

After exceeding the climate targets set in 2017 and then raised in 2021, La Caisse has developed a new strategy to accelerate the decarbonization of companies and significantly increase its investments linked to the energy transition by 2030, both in Québec and internationally. The objective remains: create sustainable value for depositors while managing the climate risks associated with its portfolio assets. La Caisse’s approach was well received by the Canadian group Shift: Action for Pension Wealth and Planet Health, which placed it first in its annual ranking.

By 2030, La Caisse aims to increase its Climate Action investments to $400 billion, in line with its commitment to carbon neutrality by 2050. This strategy is based both on investments in companies that clearly and credibly integrate climate issues into their business model, and on investments in climate solutions, i.e. companies, activities or technologies that help reduce carbon emissions. To find out more, visit this page or see the Sustainable Investing Report to be published in spring 2026.

Financial reportingThe costs incurred by La Caisse to conduct its activities include operating expenses, external management fees and transaction costs. In 2025, operating expenses decreased to 21 cents per $100 of average net assets, compared with 23 cents in 2024 and 26 cents in 2023. This significant reduction in the operating expenses over the past two years reflects the efficiency efforts made by the organization, particularly since the integration of its real estate subsidiaries. The total cost of internal and external investment management is 74 cents per $100 of average net assets as at December 31, 2025, compared with 67 cents in 2024 and 83 cents in 2023. Note that this figure varies depending on different factors, such as asset size, transaction volume and external management fees paid. Cost management remains a priority for the organization and, based on external data, La Caisse’s cost ratio is among the lowest in the industry.

The credit rating agencies reaffirmed La Caisse’s investment-grade ratings with a stable outlook, namely AAA (DBRS), AAA (S&P), Aaa (Moody’s) and AAA (Fitch Ratings).

About La Caisse

At La Caisse, formerly CDPQ, we have invested for 60 years with a dual mandate: generate optimal long-term returns for our 48 depositors, who represent over 6 million Quebecers, and contribute to Québec’s economic development.

As a global investment group, we’re active in the major financial markets, private equity, infrastructure, real estate and private credit. As at December 31, 2025, La Caisse’s net assets totalled CAD 517 billion. For more information, visit lacaisse.com or consult our LinkedIn or Instagram pages.

La Caisse is a registered trademark of Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec that is protected in Canada and other jurisdictions and licensed for use by its subsidiaries.

And here are the slides that accompanied the press conference this morning:

The slides provide a great snapshot of key activities by asset class and overall returns and along with the comments Charles Emond, Kim Thomassin and Vincent Delisle made during the press conference, I think they covered it all very well.

I would urge all of Canada's Maple 8 to do the same thing and post your press conferences on YouTube just like Norway's NBIM does.

I'll give La Caisse's Communications department an A for this press conference (A+ if they post it on YouTube).

Discussing 2025 Results With Vincent Delisle, Head of Liquid Markets at La Caisse

This afternoon, I had a chance to talk results and markets with Vincent Delisle, Head of Liquid Markets at La Caisse.

I want to thank him and Conrad Harrington who set up the Teams meeting.

Vincent began by giving me an overview of the results:

We're quite happy with the results. The RRQ, the CPP equivalent, comes in close to 10%. These results exceed the ask from our depositors. The funds are well funded, in very, very good health. What we're seeing is some strong returns from Public Equities, Infra and Credit which had a had a great year. Real Estate, still tough, but better than it was last year. Private Equity is somewhat disappointing for the year, coming in at 2% but it's been a significant tailwind in terms of performance on a 5 and 10 year horizon. Our business is to have a diversified portfolio focused on requirements from our depositors, adjusted for risk. So we're happy with the returns that we generated in today's environment where public equities had another stellar year in 2025, so it's been three years of very robust performing for all things public equities. It has an impact on our value added, because obviously our private portfolios -- private equity portfolios, benchmarked against that, Infra as well. So these are, these are challenges for our industry in terms of how the performance is perceived and and received, but we're quite happy with how we executed last year.

I then asked Vincent specifically about PE: "A couple questions here on private equity. I don't know if you even know this. Were the returns mostly due to significant write downs taken in one or two investments, or was it just broad based valuation contraction of the multiples?"

He responded"

When you look at the private equity portfolio, profit growth for our companies was up six to 7% which is pretty much in line with what we're seeing in the industry. Valuations were hit by rising interest rates and there were one or two writedowns that took the numbers down from 6-7% to 2%.

In Real Estate, I told him I heard Charles say this morning that they sold some office towers in the US and he confirmed this:

Yes, we had some strategic dispositions in the US, absolutely. The key turnaround for this team in this portfolio, is going from a real estate operator to a real estate investor. And we were, we're rejigging the philosophy of this portfolio, rebuilding the team while the industry is going through some very, very challenging times. The numbers last year basically flattish on the year, better than what we did the year prior, at minus 11%, but it's still navigating within an industry that is see some significant headwinds.

I asked him what the split is at the Caisse between private and public markets and off the top of his head he said roughly 65/35 public vs private.

I then stated private credit and emerging market debt boosted the returns of the Credit portfolio and asked him to give me a bit more flavour there.

He shared this:

Just to be clear for us, Liquid markets includes public equities and all of fixed income, including private credit. So why is that? Our private loans mature within two to three years, so we get the liquidity coming back quite quickly. The emphasis here on liquid markets and then public. The credit portfolio had a stellar year in 2025, 9.6% absolute return outperformance relative to its benchmark and the way that portfolio has been structured from day one in 2017 was a hybrid between public credit and private credit.

We do a lot of arbitrage to make sure that the premium that we're getting on the private side is worth, you know, giving away the liquidity. And we also have a the emerging market debt strategy in there that brings a very solid construction to the credit portfolio. It also brings volatility. I'm not going to lie to you, but when things work out like they did last year, we ticked all the boxes on the on the credit side. We didn't start doing emerging market debt last year. We've been doing it since 2017. What worked for us, or for emerging market debt in 2025 is a is basically a combination of two things, yields went down in markets in countries like Colombia, Brazil and Mexico, and their currencies appreciated. We had not seen that double that positive combo in recent years, so that was a significant driver of performance. On the private credit side, it was still a very, very, very good year, but the contribution from emerging market debt is really where the outperformance came from in 2025.

I asked him if he could give me the breakdown of the Credit portfolio which he did:

As of December 31 2025, 56% of the credit portfolio is allocated to privates, and remaining 44% is on the on the public side. Every year we're in our strategic plan. The goal, the objective, is to deploy $20 to $22 billion to new loans on the on the private side. In recent years, the amount of refinancing has been very elevated. So, for instance, last year we deployed $21 billion, we got $17 billion in refinancing, so the net increase was only $4 billion. But the teams can deploy, you know, they're very solid. The deployment is allocated to bank loans, direct lending, infrastructure debt, real estate debt, and also capital solutions team.

I told him I did see they are looking to double the private credit portfolio over the next five years and asked him if that's feasible.

He replied:

It is feasible we can deploy. The teams are deploying north of $20 billion a year right now, getting north of $20 billion,we need refinancings to slow. And the thing we don't control is what happens on the public side. The key differentiator when you look at our credit portfolio relative to the Maple 8s, I think there are two differentiation. We do emerging market debt in there on the credit side, and we, we have the pool of public and private under the same house. There's an arbitrage. Every single deal that comes true has to be the public benchmark. I'm mentioning this because if credit spreads on the public side widen significantly, there will be a period where we're not going to allocate as aggressively on the credit side, but the strategic planning takes us above $120 billion.

He added:

I think is very, very smart. And the portfolio was built that way in 2017 and we've seen instances where spreads widen significantly, and we can dial down, the tap, and then we dialed it back, back up. I think it's significant advantage.

I moved on to public equities where I read they were underweight gold shares and some Quebec stocks cost them some performance last year.

Vincent replied:

When you, when you look at the performance of our public equity portfolio, we outperform the MSCI World, and we outperformed the MSCI Emerging Markets. So our internal teams, our external teams, added value. It is a very tough environment to add value, and when you look at our positioning relative to the world, we're second quartile. And I'm very proud of that. The mandate where we had more difficulties last year was our Canadian mandate. We have some exposure to gold, but not to the same extent as the as the benchmark and a few Quebec stocks had more difficult years on a relative basis, that's the only mandate where we underperformed last year. So all things global, and I'm always very proud to mention this, but 100% of what we manage global and em internally, is managed here from our offices in Montreal, by our by our quant teams and fundamental teams, and they, they had a great year.

He told me their benchmark is MSCI Acqui for 80% and 20% is a Canada benchmark because their home bias and the large position they have in Canada.

We moved on to US stocks where I noted concentration risk was high again last year. I noted this year software stocks are getting slammed and chip stocks, especially memory, are surging again.

Vincent noted the following:

There are a lot of things going on. So let me touch on a few topics, concentration and how it is making it challenging for investors. There's two concepts of concentration, the one that was very challenging form 2020 to 2024, was the concentration in the benchmark that was going up, so the FANGs become the Mag-7s, and all of a sudden, you know, the Mag-7s account for 33% or so of the S&P 500.

The other aspect of concentration is concentration of gains. And even though the Mag-7s last year did not dominate. The concentration of gains was very, very high. So you take the time the 10 largest contributors to the S&P 500 last year, you get the 68% it was north of 50 in 2024 and 2023. In your average year, pre-Covid, you're running at 25 to 30% so that aspect, when you have a diversified portfolio, makes it very tough.

How do we navigate this? In 2020 we had very little technology exposure. We had to do something. 2021, 2022 and 2023 we significantly increased our US / tech exposure, and we kind of capped it off in 2024 and in 2025 we reduced our US exposure as I mentioned this morning.

We're trying to play that. We're trying, but we're much more selective in how we we get exposure to the AI thematic, the technology thematic. We find better opportunities outside the US. We don't want to play the hyperscalers just being naive and chasing the hyperscalers. So last year, what helped us is we reallocated some US exposure into European financials, Korean tech, Taiwan tech and Japanese industrials and financials.

On AI. AI has been dominating everything since 2022 but the way AI dominates has changed significantly since last fall. And this year, it's quite amazing to see what's going on, because the big spenders, hyperscaler spenders, are not getting the retribution anymore. There's the market's much more selective and doesn't give the benefit of the doubt to everybody that's spending like like crazy, and then you have a whole SWAT of industries that are getting penalized because of the fear of of disruption.

Our thesis is that we think the markets can still move a bit higher but our thesis is that there's, there will be broadening of leadership. And there are many, many sector that have been left for dead in the last few years that are coming back alive this year. So the rotation is, is very visible year to date, not only geographically. Last year was more geography, but this year is more on the sectoral basis, energy, materials, transports, consumer staples, REITs. These are all names that have not been talked about leadership in in recent years. So very selective on how we play AI geographically, more more opportunistic on the EAFE space, and broadening participation is how we try to align our portfolios.

I noted the S&P Equal Weight Index (RSP) is outperforming the S&P 500 (SPY) this year and this is a good environment for active managers.

Vincent shared this:

The environment of a concentration disadvantage that was prevailing in recent years, having the US equal weight outperforming the market cap weighting is going to make life easier for portfolios that are more diversified. And look at the spread right now on my screen, RSP plus six. Spider up one. Yes, it is an environment where actually being be more prudent. And, you know, diversifying within sectors and geography makes it, makes it easier to beat the benchmarks.

I told him that we are only two months into the year and things can change on a dime so it's too early to predict the end of tech this year.

He added:

We must not prematurely call it over. It kind of started in Q4 and it accelerated in January and February. And from our standpoint, the reason why this rotation has been ongoing is twofold. First, there's some signs of life, nascent signs of life in US and global manufacturing, the PMIs and the the ISMs have been in recession for over three years. The New Order components are now back above 50. If we get an ISM increasing type of market this year, then more cyclical, the real economy sectors should perform better. And the other reason why, we had to give credence and weight to this rotation out of tech. It's getting more complicated within the tech sector as well. Software is getting killed. Memory is skyrocketing every day, the hyperscalers, some are performing, others not. So it would be, would it be surprising to see tech as a whole come back with the same extent of domination, but it could happen.

But he added:

Software is certainly one area where you have to ask yourself, is the selloff overdone? Because there's no doubt companies in every area will be changed by what AI brings to the table. But the speed at which we've seen market cap evaporate in many, many industries, it begs the question, how much is too much? Right?

Lastly, I asked him what worries him in terms of the macro environment?

Vincent shared his concerns:

Interest rates is where I keep my focus. I'm worried that eventually we can't have our cake and eat it too like we have. We can't have an economy that gets somewhat better and rates moving moving lower. 2025 was all about tariff shock. 2025 was all about central banks cutting rates aggressively. 2026 could see some slight improvements in global growth, exports, trade, manufacturing. If that happens, then we start pricing the next move from central banks in 27/28.

I am more focused on what changes the trend in interest rates. You know, we've been living with so many fears and headlines over the recent years. You know, tariffs, wars in the Middle East. I'm paying very close attention to oil, because oil doesn't get enough credit for how inflation was tame last year. Oil is up 15% one five. Year to date, it's only late February, that that could throw a wrench into the pretty inflation picture that we have.

I asked him what he thinks about AI unleashing a massive deflationary wave and he said this:

Well, it's hard to argue against that because we don't have any concrete evidence yet. AI will certainly have the same positive impact on productivity as what we saw with with technology, the internet, in the 2000s and 2010. Then you have these, you know, population, immigration, you know constraints. Look at Japan, look at the US, look at Canada. I wouldn't say it's smooth sailing for inflation just because AI is, is upon us.

Great food for thought, so pay attention to oil and rates as they might be moving up over the next two years.

I wrapped it up there and thanked Vincent and Conrad.

Conrad subsequently responded to an email question of mine on currency hedging and how much the slide in the US dollar cost them last year:

Regarding currency hedging, we partially hedged the USD exposure. Through this partial hedge, we protected $3,6 billion. The USD had a negative impact of around $6 billion (it would have been close to $10 without hedging). Please see the find the relevant section from our press release (see above).

Alright, that's a wrap.

Below,The Caisse posted an annual return of 9.3% for 2025, a result that, however, fell short of its benchmark portfolio's return of 10.9%, due to "geopolitical tensions" and "persistent tariff uncertainty."

This difference compared to its benchmark portfolio means that the Caisse's return in 2025 was lower than that of the financial indices to which it compares its performance.

Nevertheless, Quebecers' savings are doing well, assures the Caisse, which points out that its five-year annualized return of 6.5% surpasses its benchmark portfolio's 6.2%. Over a 10-year period, the Caisse posted an annualized return of 7.2%, while its benchmark portfolio's return was 6.9%.

RDI's Olivier Bourque explains the details (in French).

I like this clip because a minute in, Charles Emond is quoted saying they're highly diversified, looking to hit singles and doubles, not home runs.

Assets by Geography

Assets by Geography Investment Performance Highlights

Investment Performance Highlights

Recent comments